Between This World and Another

Mary Hall Surface: Talking about literary first-loves and real life

Welcome to STRANGE LITTLE STORIES, where writers can share real-life incidents that haunt them, memorable events, peculiar occurrences, uneasy encounters, the kind of thing writers usually transform into fiction. Here, we give them a chance to focus on the raw material of real life, to discuss what makes these memories so indelible, and examine the mysterious relationship between truth and fiction.

This time it’s a real pleasure to welcome Mary Hall Surface, playwright, theatre director, and arts educator. Mary Hall has presented her creative and reflective writing workshops at the National Gallery of Art, the Smithsonian Associates, Washington National Cathedral, the Chautauqua Institution as a Writer-in-Residence, and at Harvard’s Project Zero Classroom. Her plays have been produced worldwide including seventeen productions at the Kennedy Center. She has published fifteen plays, an anthology of her scripts, and three original cast albums. She also leads Writers’ Studios on the Amalfi Coast of Italy, the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts, and in Taos & Santa Fe, New Mexico.

She is (as you can see) quite busy. ;-) And I’m very glad that she made time to be the December guest-writer here at STRANGE LITTLE STORIES.

In this brand new story written especially for SLS, Mary Hall describes a powerful experience she had in the home of one of our literary heroes, Charles Dickens. Afterwards, she and I chat about literary first-loves, the thin veil between the past and the present and between one world and another, plus some sisterly-brotherly stuff. I hope you enjoy it as much as we did.

Pilgrimage

by Mary Hall Surface

By the time I was ten, I knew whole passages of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol by heart. My brother David knew more. As young children we listened to our mother’s three-record set as the voice of Lionel Barrymore conjured Scrooge. We sat on the floor by the record player to be close to the story we first illustrated with our imaginations. Later, we had an abridged edition with a shiny blue cover. Even as adults coming back to our parents’ house, David would find it to read on Christmas Eve. In high school, when I adapted the story for the stage, the words felt like my mother tongue. And the black and white brilliance of Alistair Sims’ Scrooge has been the centerpiece of our family’s Christmas night for as long as I can remember.

So, on my first trip to London, naturally I wanted to do all things Dickens. I was nineteen and studying theater during a winter term in college. While my classmates were eager to go with me to Ye Old Chesshire Cheese, a pub that Dickens frequented, they were less interested in my pilgrimage to the Dickens House Museum. So I went alone. I had to. I was sure if I could step into the world of my literary first love, I would find the blessing I was looking for to become a writer. Why else do we preserve the houses, the desks, the pens of famous writers? Yes, to honor their legacy. And to keep them alive. We long to meet them beyond the page.

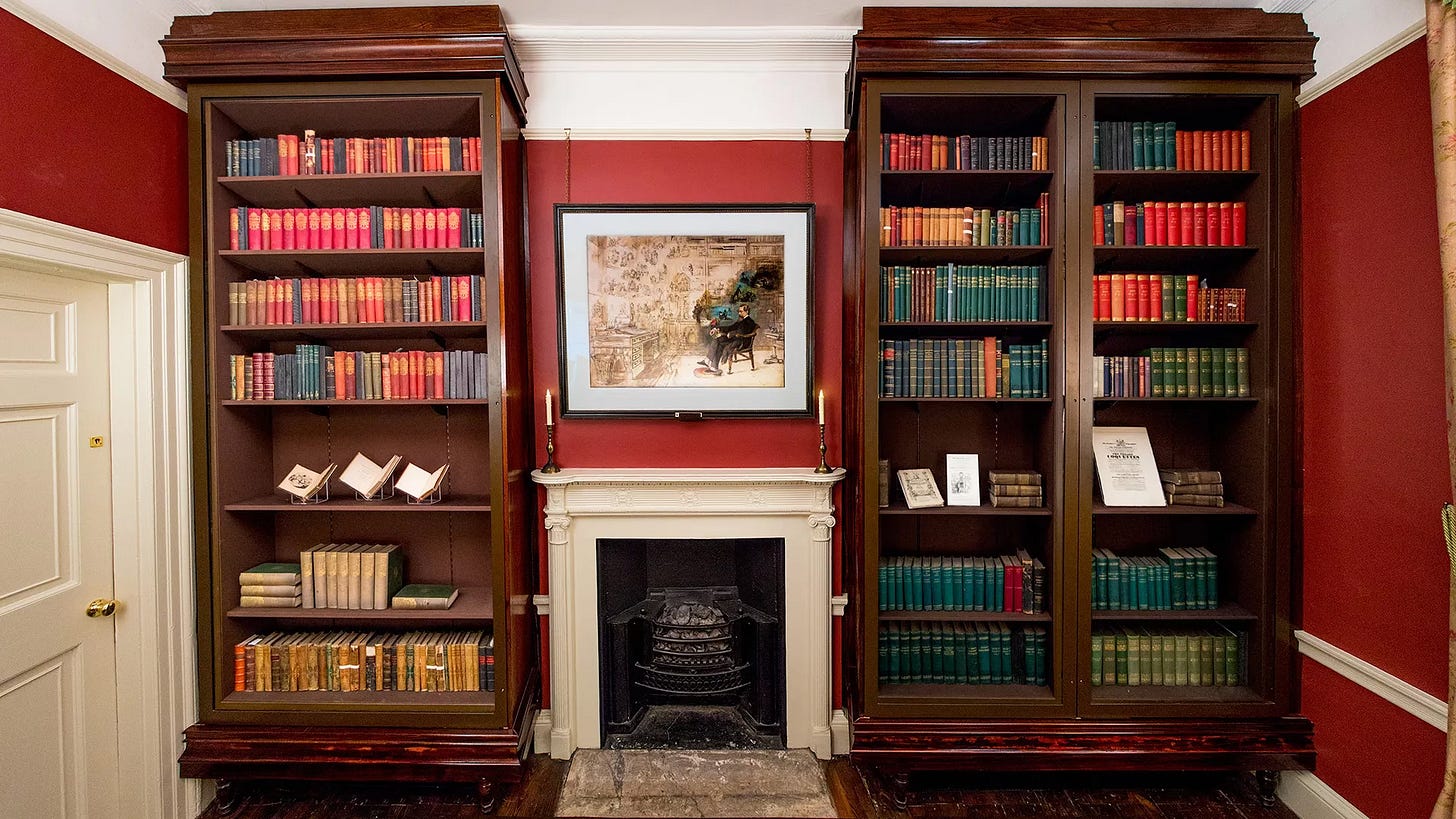

I got myself to Gray’s Inn Road, a name that matched the sky on this February late afternoon. Around the corner on Doughty Street, I find the terraced Georgian house where Dickens had lived. I stop, as if before a shrine, and whisper, “here Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby were born.” I resist my theatrical impulse to genuflect. I walk in, buy my ticket, and discover I am the only visitor.

I step into the entry hallway filled with artifacts – Dickens’ cane, his money purse. The dim lights, necessary to preserve the objects, give the whole space a patina of the past. Once in the dining room, I see a table set for a party of Dickens’ admirers, eager to dine with the 25-year-old literary sensation. I imagine a pudding being served, prepared in the copper in the kitchen below, like the Cratchit’s on Christmas Eve.

Passing the morning room with its portraits of young Dickens and his wife, Catherine, I see something odd. A gray silhouette of a man is painted on the wall at the base of the stairs, one foot poised on the first step, one hand gesturing toward the next floor. This flat spectral figure offends me. I don’t need this obvious invitation to imagine Dickens’ presence. It’s demeaning. And oddly disturbing. I quickly pass this shadow as I ascend the stairs.

In the drawing room I picture a room full of guests, one at the piano, the others dancing, a polka surely. I hear the laughter of games and charades. I long to touch the small desk under plexiglass in the corner, the one Dickens designed for his public readings. A copy of his reading script is open to, what else, a scene from A Christmas Carol. As I reach toward the pages, I feel a draft of cold air. Not unusual for an old house. I zip up my coat and turn toward the inner sanctum.

Dickens’ study is warm, welcoming, almost familiar. I stand next to his mahogany desk with its sloped writing surface. I see his glass inkwell always with blue ink. His goose quill pen. His silver magnifying glass. I imagine him spinning round to leap from his desk chair to act out his characters as he writes. I do the same thing because of him.

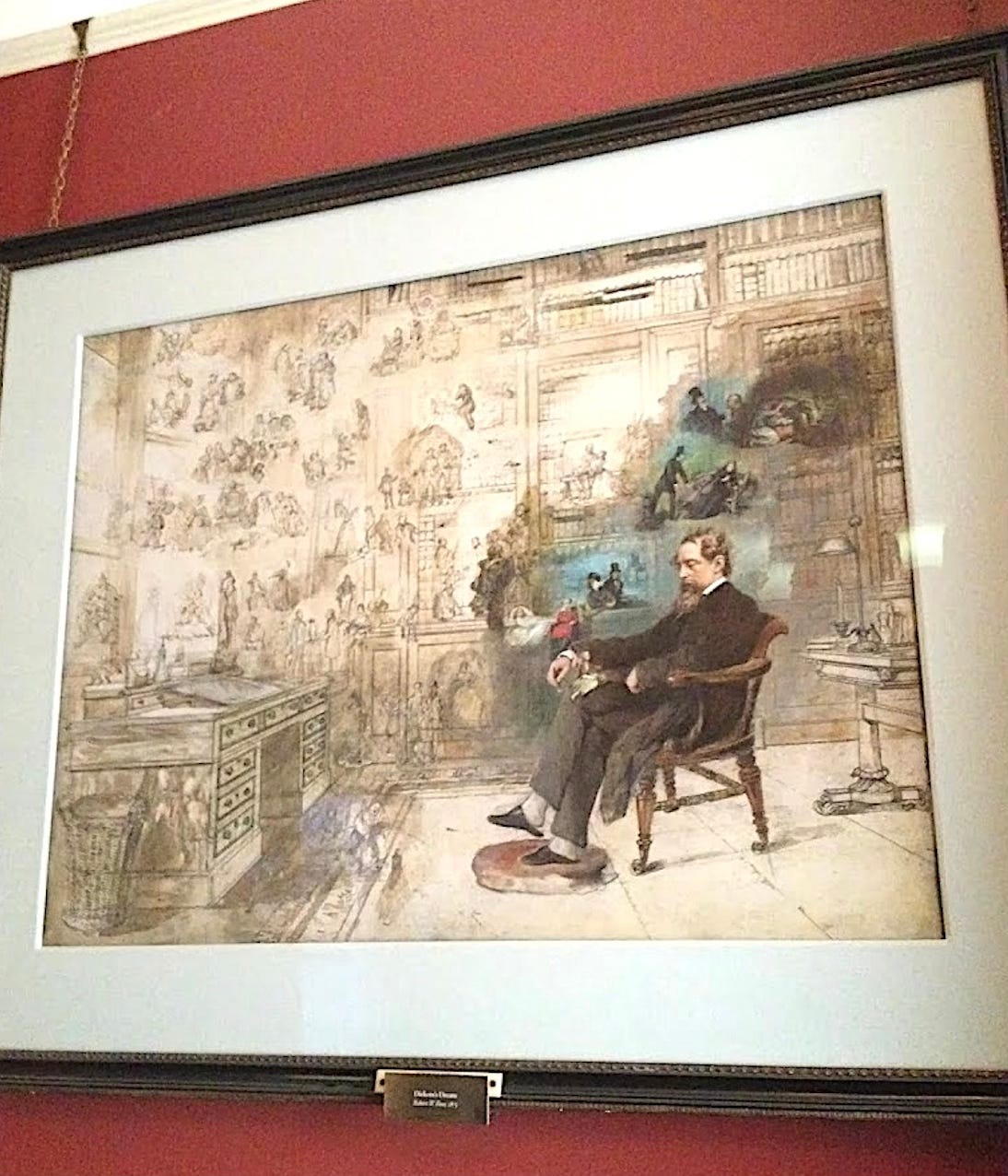

Over the fireplace, I spot the famous watercolor in which Dickens sits in his chair, eyes closed, as over fifty small figures depicting his characters float above his desk and around him. The figures closest to Dickens are in color. The others recede into sepia tones. At first, the characters seem like enchanting fairies rising from the great writer’s dreams. But the longer I look in the shadowy light, they change. They become phantoms to me, like the wandering spirits that Marley shows to Scrooge. Imprisoned between worlds for eternity. When I recognize one of the figures closest to Dickens to be Little Nell on her deathbed from The Old Curiosity Shop, again I feel a rush of cold air. Stronger than before. I move to the other side of the study to step out of the draft. But now the whole room feels chilled. Maybe it will be warmer upstairs. I decide to come back later to the study.

I jump when I see the Dickens silhouette at the base of the stairs. He beckons me up to the family’s most personal spaces. The dressing room where Dickens prepared to meet his public. The bedroom where Catherine gave birth to two of their ten children. Then I enter a small bedroom where a woman’s white gown is displayed on the bed. On the vanity, I see a hairbrush and mirror but also a pen and ink. The signage introduces me to Mary Hogarth, the younger sister of Dickens’ wife who came to live with them soon after they were married. I learn that Dickens adored Mary for her strong opinions and trusted her to read the first drafts of Oliver Twist and Pickwick Papers. But after attending a night at the theater together, she collapsed and died in his arms a few hours later in this very room. She was seventeen. Perhaps it is her age so close to mine, perhaps the pen and ink. Did she want to be a writer, too? Suddenly she is more real to me than the ghost I came to find. The room fills with a coldness sharper than before. I try to leave the room but cannot. I feel my breath grow shallow and fast. I gasp into the cold air, “I will know you.” This promise releases me. I almost tumble down the stairs, defying the silhouettes. I pass Dickens’ study without stopping on my way out the door.

I kept my promise. I learned that after her death Mary Hogarth was the model for the sweet, perfect young women in all of Dickens’ fiction. She is Little Nell. She is Kate Nickleby in Nicholas Nickleby. She is Agnes Wickfield in David Copperfield. Could this young woman, who was prized by Dickens for her bright mind in life, resent being reduced to a sentimental ideal in death? Is she imprisoned, too? A wandering spirit? I even wondered, as a young playwright, if how I write women could help set her free. That wonder was and remains a blessing.

DS: Hey, Mary Hall! Thanks again for your terrific story. When I asked you to come up with a “strange but true” tale, about how long did it take you to settle on this one? What “route” did your mind take to arrive at it?

MHS: As soon as you told me about your “Strange Little Stories” series, I thought immediately of this story. For while I love to seek out places where the veil is thin between past and present, or this world and another, I’ve never had an encounter as vivid and as consequential as the one I describe. I also was drawn to the story because it begins with us as children, which I thought your readers might enjoy.

DS: Yes, I certainly enjoyed that too! :-) I actually think a lot about how you and I grew up with a lot of the same models for how a good story should be told. Dickens (A Christmas Carol, of course) was a kind of north star in that firmament––Rogers and Hammerstein (not to mention Lerner and Loewe) certainly left a mark on us too. I think it’s probably true that most young writers model their first stories after favorite stories they’ve read and seen. (Nothing wrong with that!) But it’s pretty rare, I think, to find a young writer who starts out writing stories about their real life, even though that material is right there in front of them. Why do you think that is?

MHS: Perhaps they don’t think it worthy of writing about — too ordinary, not sufficiently fascinating. That said, for the young playwrights I work with, especially teenagers and young adults, their “real life” is most often what they want to write about. In one class I finally said, “no plays set in the cafeteria or dining hall.” Unfair of me, perhaps. But I was eager for these young writers to stretch beyond being reporters of their lives and to explore worlds beyond their everyday, even if that world is a more imaginative way of perceiving their real lives.

And, I would add that, to me, our real lives include the subjects and notions about which we are most passionate or have the deepest questions. Stories and plays about those things don’t feel separate from the writer to me. They feel very much a part of what is most real. That’s certainly how I began as a playwright. And maybe my expansive definition of “real life” comes from realizing, just now, that in 40 years of writing, only one of my plays has been set in Kentucky. Interesting! My lived experience absolutely informs and shapes my writing, but it has never been the content. Except for this story.

DS: What a fabulous answer! I really love your “expansive definition of real life”, and how you say that stories and plays “feel very much a part of what is most real”. I think that for some of us (and I know this is part of what you’re saying) it’s in these ‘received’ stories written by others that we tend to experience our own lives most vividly and fully. So (like I said) I really love your take on that.

Speaking of your lived experience shaping and informing your writing, I’m guessing that a lot of that tends to be a general sense of the kinds of events, thoughts, and feelings that tend to pop up in your life, which are then sort of “reincarnated” in different guises. I’m just wondering––what’s the closest you think you’ve come to lifting an actual event or moment from real life and weaving it into your writing (while changing very little)?

MHS: Yes, I’ve always felt that I experience my life most vividly and fully through the stories I imagine. That said, I did write a play that was very much centered on an event and relationship in my life.

Early in my career as a theatre educator, I had student, Whitney, with significant learning challenges. Her parents had told me not to ask her to read out loud. But this 8-year-old, the youngest in our summer conservatory, had written a poem along with the other students. She seemed excited by the process, so I encouraged her to read hers. I remember thinking, “She wrote it, surely she can read it.” I was wrong. She struggled until her brother appeared at her side and helped her through it. I am not sure who felt more shame in that moment — Whitney or me.

Whitney stayed in our conservatory for six years, evolving into a wonderful actress. We talked openly and deeply about how she navigated the world. I ultimately wrote a play called Blessings for our professional company, in which she played a character based on herself, a fourteen-year-old artist with an auditory processing disorder and severe dyslexia. Interesting, too, that much of the dynamics of the adults in that play, who were high school friends having a weekend reunion, were based on my high school years. So lots of real-life weaving with that play.

Perhaps next up, I’ll write one about a little girl who grew up with a big brother who liked to scare her with strange big stories. Spoiler: She survives, imagination fully intact :)

DS: Ha! Guilty as charged! ;-)

Sounds like lots of real-life weaving went into that play. And weaving elements of your life into Whitney’s must have been amazing. BTW, let me take this opportunity to publicly express my regrets for all the childhood traumas I may have inflicted on you with all my monster-y stuff! You did indeed survive it, and your imagination is far more than fully intact. :-)

Thanks again for your terrific strange little story, and for chatting about it with me. It’s been lots of fun! And when I finally make it to Great Britain, I’ll go and pay my respects to our mutual imaginary uncle, Mr. Dickens. I’ll be sure to tell him you said hi.

Thanks again - oxo

Many thanks to Mary Hall Surface for joining us at STRANGE LITTLE STORIES. If you’d like to learn more about Mary Hall and her writing and teaching, you can visit her website here.

And, just another reminder that my new collection These Things That Walk Behind Me from Lethe Press is now available from Amazon or direct from the publisher. Hope you’ll check it out.

Thanks for reading STRANGE LITTLE STORIES. See you next time.

Thank you for sharing your experience and insights. I felt like I was there too.

I felt my family room grow colder now as I read your essay, Mary Hall. I am sure this room in my house is a portal as is my master bedroom which sits upstairs over the family room. I have had a few visitations of loved ones and at least two strangers who had already passed.